Coverage by Chris “Maven” Austin, excerpted from this post at Maven’s Notebook:

At the January meeting of the California Water Commission, Taryn Ravazzini and Dane Mathis from the Department of Water Resources Sustainable Groundwater Management Program were on hand to brief the commissioners on the draft decisions on the 2018 groundwater basin boundary modifications.

The purpose of the presentation is to hear comment from the commissioners and the public, but it should be noted that in this instance, the Commission does not have an approval role in the Department’s decisions on basin boundaries.

Groundwater basin boundaries are foundational to implementing SGMA because they define the area to managed and modifications to basin boundaries are solely at the request of local agencies.

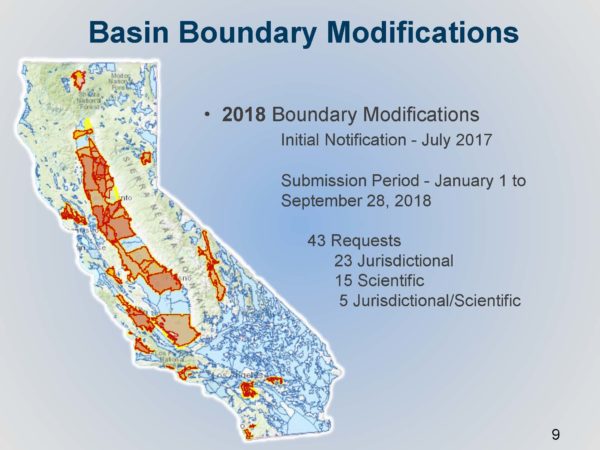

This is the second round of basin boundary modifications that has occurred since the regulations were adopted; the first round was conducted in 2016. The period for applying for modifications began on July 1, 2017 and closed on September 28, 2018.

Modifying a groundwater basin’s boundaries potentially affects the basin prioritization which is a ranking of the state’s groundwater basin based on eight factors, such as population, the number of water wells, the degree that the overlying population depends on groundwater, irrigated acreage, and others. Those basins with a high and medium priority are subject to SGMA. Basin boundary modifications must be finalized before the prioritization can be finalized.

Modifying a groundwater basin’s boundaries potentially affects the basin prioritization which is a ranking of the state’s groundwater basin based on eight factors, such as population, the number of water wells, the degree that the overlying population depends on groundwater, irrigated acreage, and others. Those basins with a high and medium priority are subject to SGMA. Basin boundary modifications must be finalized before the prioritization can be finalized.

There are 59 basins whose basin prioritizations could potentially change because they are either requesting basin boundary modifications or would be potentially affected by the results. On January 4, 2019, the Department released the final prioritization for 458 basins who are not impacted by the requested basin modifications. After the basin boundary modifications are finalized, the remaining basin prioritization for the 59 basins will be released; that is expected later this spring.

BASIC DEFINITIONS

A groundwater basin is defined as an aquifer or stacked aquifers with reasonably defined  boundaries in a lateral direction and with a definable bottom. An aquifer refers to sedimentary rock or alluvial sediments that can produce a significant economic quantities of groundwater.

boundaries in a lateral direction and with a definable bottom. An aquifer refers to sedimentary rock or alluvial sediments that can produce a significant economic quantities of groundwater.

The basin’s external boundaries are based upon science and presumably the best available science that we have. However, a basin can be subdivided along lines that reflect jurisdictional or institutional boundaries such as a county line or a water district boundary.

“A basin in itself is not necessarily defined by the land use, whether or not there may or may not be productive wells within the material,” said Mr. Mathis. “It’s not necessarily defined by the presence of a stream channel or perhaps habitat.”

BASIN BOUNDARY MODIFICATION REQUESTS

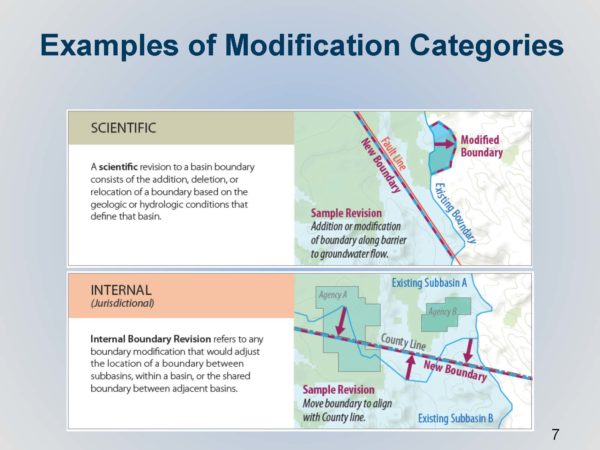

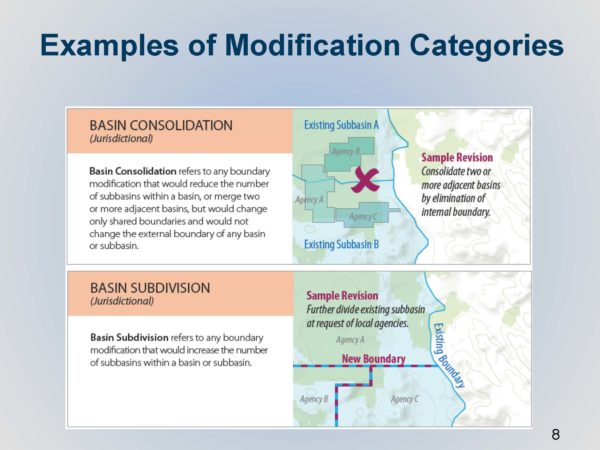

Basin boundary modification requests can be either scientific or jurisdictional. Scientific revisions are generally to a basin’s external boundaries, although sometimes an internal boundary can be modified based on a hydrogeologic barrier or some other groundwater divide. Jurisdictional modifications are based on other factors, such as moving an internal subbasin boundary from a river to a county line.

Basins may request that an internal basin boundary gets dissolved or removed, therefore creating a larger basin; alternatively, basins may request to be subdivided into smaller parts.

The Department received 43 individual requests from agencies; 23 of those were jurisdictional, 15 were scientific, and 5 were a combination of both jurisdictional and scientific modifications. The map (below, left) highlights in red and yellow the extent of requests that came into the Department. A wide range of modification requests were received, such as agency requesting an update to only a small segment, or changing a segment from the center of a river line to a county, to requests for basin consolidations.

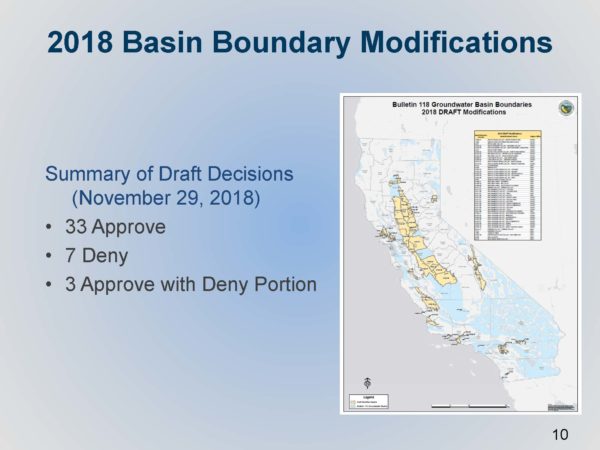

The Department then conducted technical reviews and released their initial draft decisions on November 29. At that time, the Department approved 33 requests, denied 7 requests, and approved 3 with denied portions as there were parts of those requests that didn’t quite meet the regulations.

There were numerous opportunities for public comment; a Groundwater Sustainability Agency’s required notice and consultation activities includes identifying all the stakeholders and interested parties and holding the required meetings. In the case of basin subdivision, agencies have to secure confirmed support from three-quarters of all agencies and all water systems in all of the affected basins that they are wanting to modify, and in some cases, that can be a very high bar to meet, Mr. Mathis said. The general expectation is the agency collects all of that input and hopefully gets the support and comes to the Department without opposition, although that is not necessarily a requirement.

Once the agency submits the modification request to DWR, that opens up a 30-day public comment opportunity to comment on the agency’s request. After DWR released the draft decisions, there was an additional public comment opportunity from November through January 4th. The Department also held a public meeting in December.

The Department received 30 comments on 12 basins. Mr. Mathis presented a slide showing how the comments were distributed. The Shasta Valley modification request on the left received the most comments, a total of 13. The Shasta Valley modification was denied, and so the comments in orange are reflective of opposition to the Department’s draft decision which is generally reflective of local support, he said. The South American Cosumnes, there was a mix of support and opposition, which was reflective of similar comments received during public comment period.

The Department received 30 comments on 12 basins. Mr. Mathis presented a slide showing how the comments were distributed. The Shasta Valley modification request on the left received the most comments, a total of 13. The Shasta Valley modification was denied, and so the comments in orange are reflective of opposition to the Department’s draft decision which is generally reflective of local support, he said. The South American Cosumnes, there was a mix of support and opposition, which was reflective of similar comments received during public comment period.

SOME NOTABLE BASIN BOUNDARY MODIFICATIONS

Mr. Mathis then gave some details on two out of the four modifications that were denied.

The Northern Delta Groundwater Sustainability Agency submitted a boundary modification request to subdivide three individual basins. On the map, the yellow line represents where the line is today, and the red line and shape is what the agency was requesting. The agency secured support, but the support for the subdivision was only focused on the agencies that were within their new proposed basin, so they did not meet that specific requirement in the regulations to get support from three-quarters of all agencies and all water systems in the affected basins. “As you can imagine, there would be hundreds of them for this particular scenario,” he said.

The Northern Delta Groundwater Sustainability Agency submitted a boundary modification request to subdivide three individual basins. On the map, the yellow line represents where the line is today, and the red line and shape is what the agency was requesting. The agency secured support, but the support for the subdivision was only focused on the agencies that were within their new proposed basin, so they did not meet that specific requirement in the regulations to get support from three-quarters of all agencies and all water systems in the affected basins. “As you can imagine, there would be hundreds of them for this particular scenario,” he said.

The Sloughhouse Resource Conservation District submitted a request for an internal jurisdictional modification. The yellow line shows the existing internal boundary line; the request request generally involves the expansion of the Consumnes Basin to the north into the southeast part of the South American subbasin. There was some opposition, both from the Sacramento Central Groundwater Authority and the City of Sacramento; the Department’s draft decision to deny also had comment. Sloughhouse RCD was opposing DWR’s decision to deny it, and Sacramento Central Groundwater Authority continued to support DWR’s decision to deny it.

The Sloughhouse Resource Conservation District submitted a request for an internal jurisdictional modification. The yellow line shows the existing internal boundary line; the request request generally involves the expansion of the Consumnes Basin to the north into the southeast part of the South American subbasin. There was some opposition, both from the Sacramento Central Groundwater Authority and the City of Sacramento; the Department’s draft decision to deny also had comment. Sloughhouse RCD was opposing DWR’s decision to deny it, and Sacramento Central Groundwater Authority continued to support DWR’s decision to deny it.

“In general, the main reason we denied it is that it did not appear to support sustainable groundwater management,” said Mr. Mathis. “That’s one of the elements in the regulations that allows the Department as a basis of denial for the request. In summary, there’s local disagreement on what needs to managed and how. The thinking was that it isn’t up to the Department to make that call; it’s really the local agencies that should work together towards meeting the requirements of SGMA. Certainly, they maybe to come back to the Department at a later time when they can show general agreement with each other.”

UPDATED DRAFT DECISIONS

A basin modification request was received from the Heritage Ranch Community Services District regarding a small portion of the Paso Robles area subbasin. On the map on the left, the circle and the yellow line show the small alluvial channel that drains into the main part of the basin. The initial request was denied because the information wasn’t quite clear about the connectivity of that portion to the aquifer that defines the basin; however, the requesting agency subsequently provided supporting information to the Department, so the draft decision was changed to approved.

A basin modification request was received from the Heritage Ranch Community Services District regarding a small portion of the Paso Robles area subbasin. On the map on the left, the circle and the yellow line show the small alluvial channel that drains into the main part of the basin. The initial request was denied because the information wasn’t quite clear about the connectivity of that portion to the aquifer that defines the basin; however, the requesting agency subsequently provided supporting information to the Department, so the draft decision was changed to approved.

The West Kern Water District submitted a basin boundary modification request for the Kern County subbasin. Most of the requested boundary modification change was an external boundary that would essentially remove or exclude the significant oil producing areas. These areas are somewhat anomalous within a basin; they aren’t quite pieces of bedrock that stick out in the center of the basin, but nonetheless it was based on the different type of land use going on. The Department initially denied the request, because it wasn’t clear about the level of connectivity that these areas potentially had with what’s considered the main aquifer of the basin. The agency submitted their additional technical comments during the period, and the Department did another round of technical review.

The West Kern Water District submitted a basin boundary modification request for the Kern County subbasin. Most of the requested boundary modification change was an external boundary that would essentially remove or exclude the significant oil producing areas. These areas are somewhat anomalous within a basin; they aren’t quite pieces of bedrock that stick out in the center of the basin, but nonetheless it was based on the different type of land use going on. The Department initially denied the request, because it wasn’t clear about the level of connectivity that these areas potentially had with what’s considered the main aquifer of the basin. The agency submitted their additional technical comments during the period, and the Department did another round of technical review.

“We did another round of reviews on the initial clarifying information,” said Mr. Mathis. “We did change our draft decision a little bit, but not the portion to approve the removal of the anticlines in the oil field areas. The approval was mostly for the perimeter older alluvial units and some older fractured rock units that we know are not indicative of aquifer material, per the regulations.”

There was a request by Siskiyou County Flood Control and Water Conservation District pertaining to an exposed expansion of the Shasta Valley. The initial request was very thorough with quite a few technical studies to demonstrate their proposed expansion of Shasta Valley, shown in yellow on the graphic; this was a quite a large expansion to the east from the existing basin. They demonstrated a thorough knowledge of the groundwater pumping in the area, the land use, and these volcanic deposits that they had presented. However, the one thing that was missing was the data or the confirmation that the volcanic deposits actually met the definition of aquifer in the regulations, which is defined in the regulation specifically as being reflective of sediments of sedimentary rock that produced economic quantities of groundwater. The agency provided clarifying information to successfully show there was a predominant presence of sediments and sedimentary material, although it’s interspersed within the sequence of volcanic deposits that contribute and make up and define the basin that they are wanting to modify. That updated draft decision is approved by the Department.

There was a request by Siskiyou County Flood Control and Water Conservation District pertaining to an exposed expansion of the Shasta Valley. The initial request was very thorough with quite a few technical studies to demonstrate their proposed expansion of Shasta Valley, shown in yellow on the graphic; this was a quite a large expansion to the east from the existing basin. They demonstrated a thorough knowledge of the groundwater pumping in the area, the land use, and these volcanic deposits that they had presented. However, the one thing that was missing was the data or the confirmation that the volcanic deposits actually met the definition of aquifer in the regulations, which is defined in the regulation specifically as being reflective of sediments of sedimentary rock that produced economic quantities of groundwater. The agency provided clarifying information to successfully show there was a predominant presence of sediments and sedimentary material, although it’s interspersed within the sequence of volcanic deposits that contribute and make up and define the basin that they are wanting to modify. That updated draft decision is approved by the Department.

IN CONCLUSION

The updated draft decisions were released on last week. Out of 43 requests, 35 were approved, four were denied, and four were approved with only portions denied. The basin boundary modifications are expected to be finalized in February.

FOR MORE INFORMATION …

Ellen Hanak delivers four priorities for managing the implementation of SGMA in the San Joaquin Valley

Ellen Hanak delivers four priorities for managing the implementation of SGMA in the San Joaquin Valley However, the San Joaquin Valley is at a pivotal point. It is ground zero for many of California’s most difficult water management problems, including groundwater overdraft, contaminated drinking water, and declines in habitat and native species. The Valley has high rates of unemployment and pockets of extreme poverty, challenges that increase when the farm economy suffers.

However, the San Joaquin Valley is at a pivotal point. It is ground zero for many of California’s most difficult water management problems, including groundwater overdraft, contaminated drinking water, and declines in habitat and native species. The Valley has high rates of unemployment and pockets of extreme poverty, challenges that increase when the farm economy suffers.

DWR updates the Commissioners on the evaluation of alternative plans, basin boundary modifications, and basin prioritization

DWR updates the Commissioners on the evaluation of alternative plans, basin boundary modifications, and basin prioritization

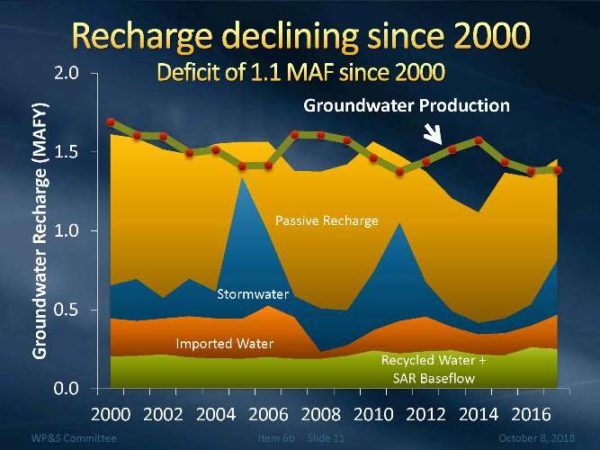

“At the October meeting of Metropolitan’s Water Planning and Stewardship Committee, Senior Engineer Matt Hacker updated the committee members on regional groundwater conditions, including groundwater production, recharge, and storage conditions.

“At the October meeting of Metropolitan’s Water Planning and Stewardship Committee, Senior Engineer Matt Hacker updated the committee members on regional groundwater conditions, including groundwater production, recharge, and storage conditions.